I didn't grow up in Tupper Lake. In fact, as a kid I knew absolutely nothing about a town that I now visit regularly, where I buy my groceries, eat fresh donuts, visit The Wild Center, and go paddling and rockhounding. I'm not a Tupper Laker, at least not in the traditional sense. In fact, I'm not even an Adirondacker based on where I was born and raised, and yet...my ancestors lived all over the Adirondacks. I am Mohawk.

As histories of the Adirondacks have changed over time, views on the presence of the Mohawk in the area have changed, too. There is a misconception that, until European explorers and pioneers started to settle in northern New York, the Adirondacks had been uninhabited, that at best the area was used as occasional hunting grounds. A few locations are known for Indigenous residents, such as Mitchell Sabbatis in Indian Lake, but Tupper Lake, like so many other locations, has been neglected. Yet bit by bit, people have been gathering together, doing research, conducting archaeological digs, and speaking out to finally get history right, to celebrate Tupper Lake as a place that has been home for thousands — not just hundreds — of years.

Going back in time

Early European explorers from England, France, and, to a certain degree, the Netherlands were overwhelmed by what they found in what is now New York. In the late 1700s, one European wrote of the land that “by reason of mountains and swamps and drowned lands is impassable and uninhabited.” Because most early explorers were daunted by the landscape and knew little about it, they asserted that the Iroquois weren’t familiar with the land, either. They said it was too harsh, too cold, too wet, too snowy. This assertion was passed along for many years, with even recent scholars and writers saying the same: that the Adirondacks had long been uninhabited due to their inhospitableness. In addition, many believed and continued to believe well into the 1900s, that the land in the Adirondacks wasn't conducive to growing crops that would have been necessary for survival.

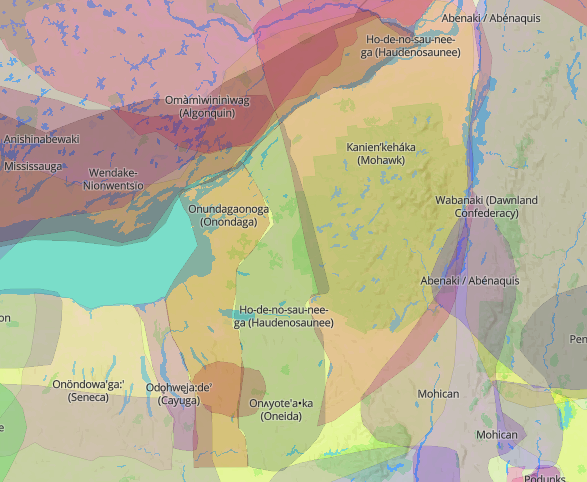

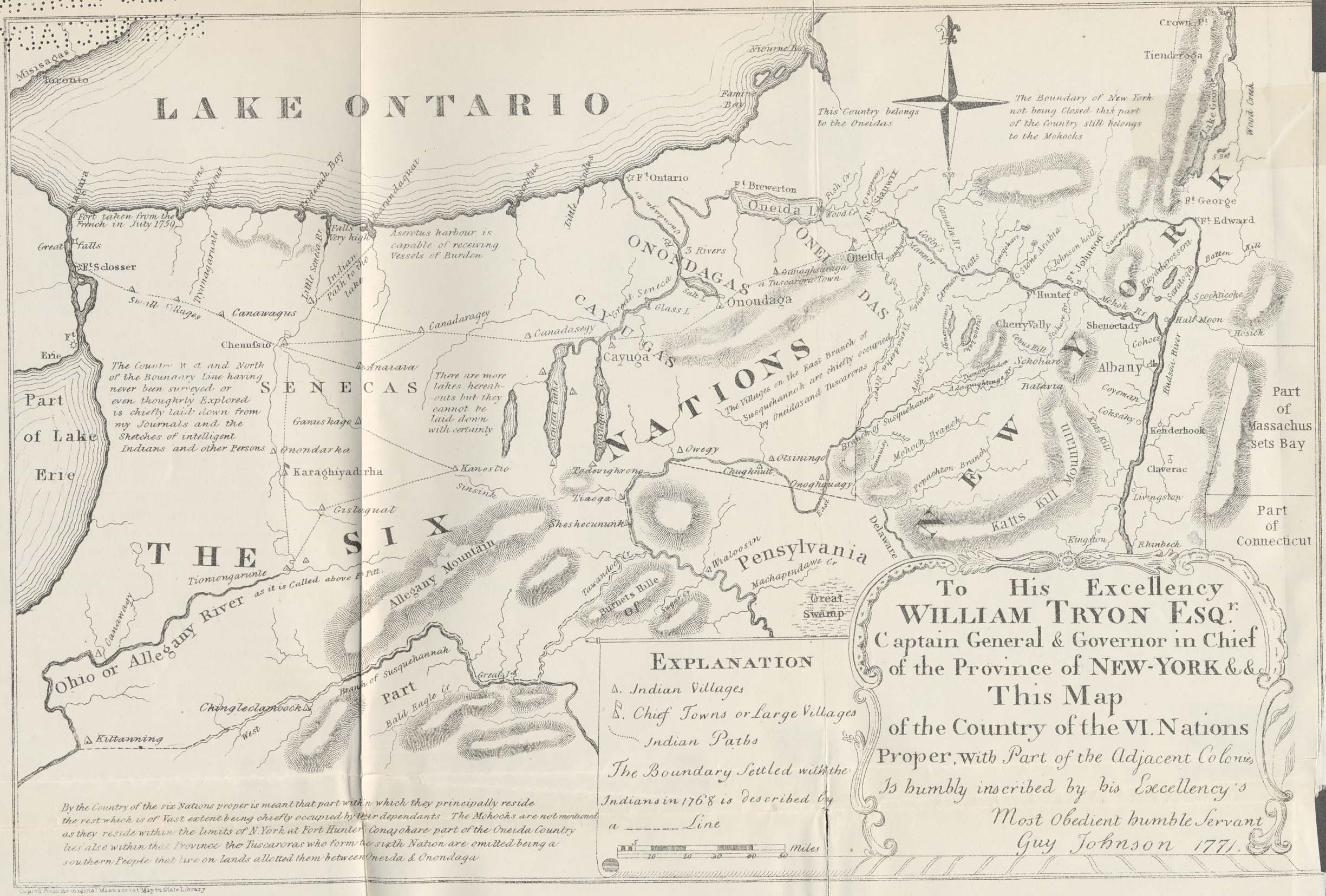

It's important to note that, at least in some ways, the presence of the nation's first peoples was not ignored. It was simply misunderstood, both willfully and subconsciously. An early map from 1771 does depict traditional homelands. The inhospitable Adirondacks are a blank space, simply marked "The boundary of New York not being closed this part of the Country still belongs to the Mohocks [sic]." At that time, the Adirondacks were apparently of little interest.

The reality, which is coming to light with increasing regularity and positivity, is that the Adirondacks were inhabited long before Europeans arrived, seeking resources to claim for kings and queens across the Atlantic. We know this thanks to people with a passion for knowledge who want to understand the complete history of this amazing area that we all love. Historian Melissa Otis is the author of the non-fiction book "Rural Indigenousness," which is full of information and excellent research. The book is a must-read for anyone with an interest in Adirondack history and is a great read, covering a variety of topics from earliest Indigenous people to loggers, entrepreneurs, and artists.

In the 1900s, there were a few people who knew about the Indigenous presence in the Adirondacks, but in many instances, they were collectors or those who found artifacts on land they owned, which they then kept as a collectible. Proper digs by trained scientists were truly rare.

SUNY Potsdam archaeology professor Timothy Messner is an excellent local advocate for exploring the Indigenous heritage and history of the area and it is people like him who are helping to make great strides in the archaeology of the Adirondacks. He has a particular interest in technology which is a great fit, as he notes, "people made and used a variety of fishing, hunting, food processing and transportation equipment. I have been using experimental archaeology to unpack the way technology made life in the Adirondacks possible thousands of years ago."

The name Mohawk is one that was adopted when Europeans traveled to the Americas. The name of our people, in the original language, is Kanien’kehá:ka, which means “people of the flint.” The flint refers to the rich resources of stone that were used for tools and arrowheads. The Adirondacks have an amazing geologic history, and its importance as a source of resources was recognized long ago by the Mohawk. It also ties in, rather poetically, to the work done by people like Dr. Messner. He has led digs and field schools in the Adirondacks, including in the Tupper Lake area, and often, the artifacts are made of flint. A field school in 2016 that took place in Tupper Lake led to a number of wonderful finds, including projectile points, scrapers, and drills.

Other artifacts have been found in Tupper Lake, including a projectile point in Piercefield. Artifacts have been found in the larger area, as well, including in Coreys, Long Lake, and St. Regis Mountain. According to Messner, "people entered the uplands as early as 12,000 years ago, and some ancient people even climbed to nearly 3000’ in elevation." Artifacts place Indigenous people in the area from 12,000 years ago up to the time when European settlers and their descendants settled in the area.

Ways of Knowing

Not everything about the Iroquois lives in the past. Today, Mohawk people live and work throughout the Adirondacks. Increasingly, people are gathering to share not just the long history but also the present and look to the future.

In 2018, the Wild Center opened a new, groundbreaking exhibit entitled Ways of Knowing. The exhibit was created in partnership with the Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center in Onchiota and the Native North American Traveling College in Akwesasne. At a recent conference in Lake Placid, Hillarie Logan-Dechene, the Wild Center's deputy director, noted that Wild Center staff felt that it was vital for the center to give the curatorial power to their Mohawk colleagues, to let them have a leading role in telling their own story. Her colleague, Penny Peters of Akwesasne Travel, shared her perspective on wanting to truly celebrate and share Mohawk culture with more people. All too often, Indigenous people have been taken advantage of, and everyone involved in the project wanted it to be fruitful for everyone.

The exhibit was designed to share the dynamic story of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and help everyone have a better understanding of and appreciation for the natural world. The multi-faceted exhibit shares Haudenosaunee teachings about living in the natural world and how we can learn from the world around us that it is part of us and we are part of it, not separate. It includes murals by Mohawk artist Dave Kanietakeron Fadden, who also runs the Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center with his family, exhibits on wetlands, traditional foods and crops, and art. Fadden's murals, the exhibit displays, and videos help tell this vital story.

It is hoped that by exploring the Ways of Knowing exhibit, visitors of all ages won't just learn about the Haudenosaunee but about our role in the natural world and how we can engage with it and seek to be better at protecting it. The Haudenosaunee people have a "Thanksgiving Address" (Ohén: ton Karihwatéhkwen) not related to the upcoming holiday but rather a greeting meant to give thanks to all aspects of the world around us. By giving the address, we can align ourselves with nature in a better, healthier way.

Part of the address, translated into English, is as follows: "We are all thankful for our Mother, the Earth, for she gives us all that we need for life. She supports our feet as we walk upon her. It gives us joy that she continues to care for us as she has from the beginning of time. To our Mother, we send greetings and thanks. Now our minds are one." You can also experience the full address in the song.

I hope you'll visit Tupper Lake, whether for the first time or the twentieth, and that when you do, you stop to think about those who lived on the land thousands of years ago, who paddled the waters, who knapped flint into tools, who loved and watched the amazing sunrises and sunsets that Tupper is so well loved for. At some point in all those years, my ancestors traveled through here, perhaps even lived here. They saw the beauty, too.